INTRODUCTION

Recognizable by its teardrop or kidney-shaped curve, often adorned with delicate internal decoration, the paisley is instantly identifiable yet infinitely adaptable. Known in India as the boteh or ambi (mango), this motif has been used for centuries ; from ancient handwoven shawls in Kashmir to psychedelic rock posters of the 1960s, the paisley’s journey is a testament to the global conversation between art, trade, and culture. Its form carries both elegance and symbolism representing fertility, eternity, and the interconnectedness of life. The curved tip of the paisley suggested movement and life—its shape subtly hinting at growth, transformation, and eternal return.

ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION

The paisley form is believed to have originated in Persia over 2,000 years ago, where it was called boteh jegheh. Its inspiration is rooted in the natural world ; some see it as a stylized floral spray, a convergence of a cypress tree and a lotus, symbolizing both strength and purity. Others link it to the mango shape in Indian art, which represents fertility and prosperity. In Persian culture, the motif often adorned royal garments and ceremonial textiles, carrying connotations of nobility and spiritual significance.

The Silk Road and the Spread of the Motif

The expansion of trade along the Silk Road carried the paisley motif across continents. By the early centuries CE, it had traveled to the Indian subcontinent, particularly to Kashmir, where artisans embraced it in the weaving of fine woolen shawls. Here, the ambi was reinterpreted in rich colors and intricate arrangements, often repeated in rows or scattered across fields of intricate floral work. These Kashmiri shawls became prized luxury goods, exported to Central Asia, the Middle East, and later to Europe. The motif’s portability ensured its adoption across cultures.

Paisley in the European Court

By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the paisley had captivated Europe. Campaigns in Egypt and Syria sparked a fascination with Eastern aesthetics, and it became a fashionable status symbol among European aristocracy. However, the high cost of importing handwoven shawls led to its local replication. Scottish mills in the town of Paisley became so proficient at producing patterned shawls that the motif itself took on the town’s name in English. These weavers modified the traditional motifs, elongating and combining them into more elaborate compositions, adapting them to contemporary tastes while retaining their Eastern exoticism.

The Motif’s Influence Across the Globe

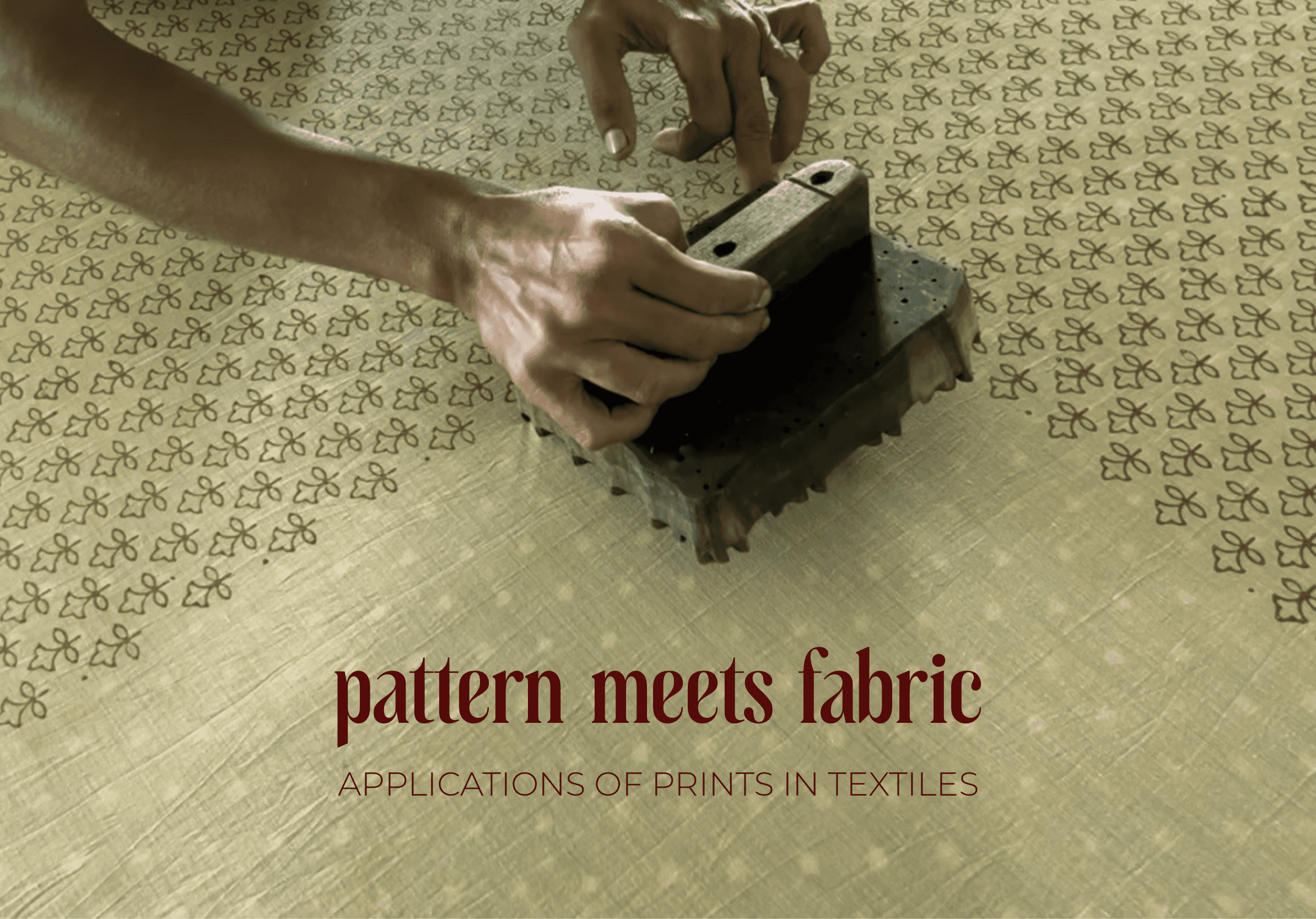

The paisley’s influence is a story of adaptation. In Turkey, it decorated carpets and ceramics; in Iran, it embellished manuscripts and royal robes; in India, it became an integral element of block printing and embroidery traditions. Each culture infused the shape with local colors, scales, and surrounding patterns. Its versatility allowed it to shift seamlessly between religious textiles, luxury fashion, and everyday household goods, always recognizably paisley, yet never bound to a single meaning.

20th Century – Reinvention and Rebellion

The paisley experienced a powerful revival in the 1960s during the counterculture movement. Musicians like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones adopted paisley-printed shirts, scarves, and stage backdrops, inspired partly by their exposure to Indian culture and spirituality. The swirling, psychedelic interpretation of paisley mirrored the era’s fascination with fluid, mind-expanding visuals. British designers such as Zandra Rhodes and brands like Liberty London reimagined paisleys with fresh palettes, softer lines, and modern repeats. It became a motif of individuality and artistic nonconformity, far removed from its original aristocratic associations.

Late 20th to 21st Century – A Global Design Language

In the late 20th century, paisley secured its place as a truly global motif. Its adaptability in scale, from delicate micro-patterns to oversized, bold prints, makes it equally suitable for couture dresses, men’s ties, yoga mats, or digital illustrations. The motif’s structure is timeless, yet its styling is endlessly customizable ; whether with flat, minimal outlines or lavish, multi-layered details.

DIGITAL AGE

Today, the paisley thrives in both traditional and digital realms. Textile designers continue to draw and paint paisleys by hand for block prints and embroidery, while others create them digitally for seamless repeats, allowing for infinite variations in color and proportion. Global marketplaces have made it easy for independent artists to sell paisley-inspired designs on clothing, stationery, and home goods. Social media has further accelerated the sharing of paisley interpretations—from minimalist Scandinavian renditions to richly layered Indian bridal fabrics.

What makes paisley timeless is its duality ; it is instantly recognizable yet endlessly reinterpretable. Designers continue to adapt it to contemporary tastes without stripping away its cultural heritage. In the world of prints, the paisley stands as both a design element and a symbol: a reminder that beauty evolves when ideas travel, merge, and are reimagined across centuries. Its journey from an ancient floral curve to a modern global icon is a celebration of creativity’s ability to transcend boundaries—proving that some shapes, once drawn, can live forever.